The US Constitution includes two oaths of office. The first—and better known one—is the presidential oath in Article Two, which reads, “I do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I will faithfully execute the Office of President of the United States, and will to the best of my Ability, preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States.” Why is “affirm” in parentheses? Because the Framers understood that an incoming president could object to swearing, indicating an oath before God, which would be forbidden. This might also explain why the Constitution does not add “so help me God” at the end, although most modern oath takers do include the phrase.

The second oath, in Article Six, similarly requires all national and state officials to “be bound by Oath or Affirmation, to support this Constitution.”

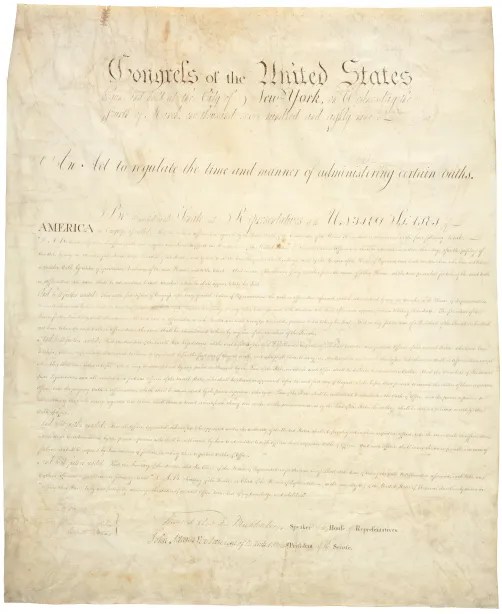

The oath taken by the vice president is not found in the Constitution. The First Congress passed an Oath Act in 1789 that specified what he (it was presumed that the vice president would always be male) should say. The current oath was adopted in 1884 and does conclude “So help me God.” It also requires that the incoming vice president swear to “support and defend the Constitution of the United States against all enemies, foreign and domestic. . .” The specific reference to domestic enemies is particularly relevant, given homeland-based insurrectionists, such as Timothy McVeigh, who planned and carried out the Oklahoma City bombing in April 1995. (If you’re wondering why the Framers didn’t refer to “enemies, foreign and domestic” in the presidential oath, the reason is that it probably did not occur to them.)

Why are these provisions for officeholders important? One answer is that, although our eighteenth-century forebears did not establish an official religion in our Constitution, they believed deeply in the significance of swearing oaths before God. Violating an oath, after all, might lead to divine, as well as secular, wrath.

Furthermore, note that allegiance is sworn to the federal Constitution. Before the American Revolution, colonial officials swore fealty to the king. Afterward, but before the Constitution was ratified in 1788, state legislatures required members to swear loyalty to their particular state. As John Adams had said, “Massachusetts is our country.” Thomas Jefferson agreed with that sentiment, saying, “Virginia is my country.”

The Framers debated which constitution—state or federal—leaders should promise to abide by. Members of the Anti-Federalist Party believed it was unfair that state officials would have to express loyalty to the federal Constitution, while officers at the national level would not have to express respect for state constitutions. The Framers also discussed whether to require oaths altogether. James Wilson of Pennsylvania argued that they were unnecessary because “a good government did not need them and a bad one. . . ought not to be supported.” The decision to specify allegiance to the federal government was a major step toward creating a union among the nearly independent states.

But there is another crucial question: Can we tell when someone is violating the oath they took? What does it mean for someone to swear or affirm to “preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States”? President Donald J. Trump was impeached twice by the House of Representatives. Did he live up to the terms of his oath or not? How do we decide?

Section Three of the Fourteenth Amendment states, “No person shall. . . hold any office, civil or military, under the United States, or under any State, who, having previously taken an oath . . . to support the Constitution of the United States, shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same, or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof.”

On January 6, 2021, an armed mob attacked the United States Capitol, where Congress was meeting to verify Joe Biden’s election, with the explicit aim of keeping Trump in office beyond January 20. Trump concluded a long and rambling speech on the National Mall, which emphasized his belief that the election had been stolen from him, by saying: “And we fight. We fight like hell. And if you don’t fight like hell, you’re not going to have a country anymore. . . So we’re going to, we’re going to walk down Pennsylvania Avenue. . . And we’re going to the Capitol.”

Did this speech mean that Trump was engaging in “insurrection or rebellion”? Jena Griswold, the secretary of state in Colorado, and the state Supreme Court believed he was and tried to prevent him from appearing on the ballot for the presidency there in 2024. The US Supreme Court, however, ruled that states cannot ban candidates from the ballot unless the US Congress passes a law giving them the authority to do so. Since Congress hasn’t passed such a law, Trump was allowed to run there. He lost the state but won the office.

Presidents will always insist that they complied with the oath. Officeholders as varied as Andrew Jackson, Abraham Lincoln, and Franklin D. Roosevelt, among others argued that they had the power to interpret the Constitution to do what they believed counted as preserving, protecting and defending it. Other people say the Supreme Court is the “ultimate interpreter” and presidents must abide by the justices’ rulings. The South African Constitution, for example, makes it clear that that country’s Constitutional Court takes precedence over any contrary assertions by the president.

What do you say? Should the president, the Supreme Court, Congress, or some other body decide whether the president has defended the Constitution to the best of their ability?

Thank you for this thoughtful piece.

LikeLike