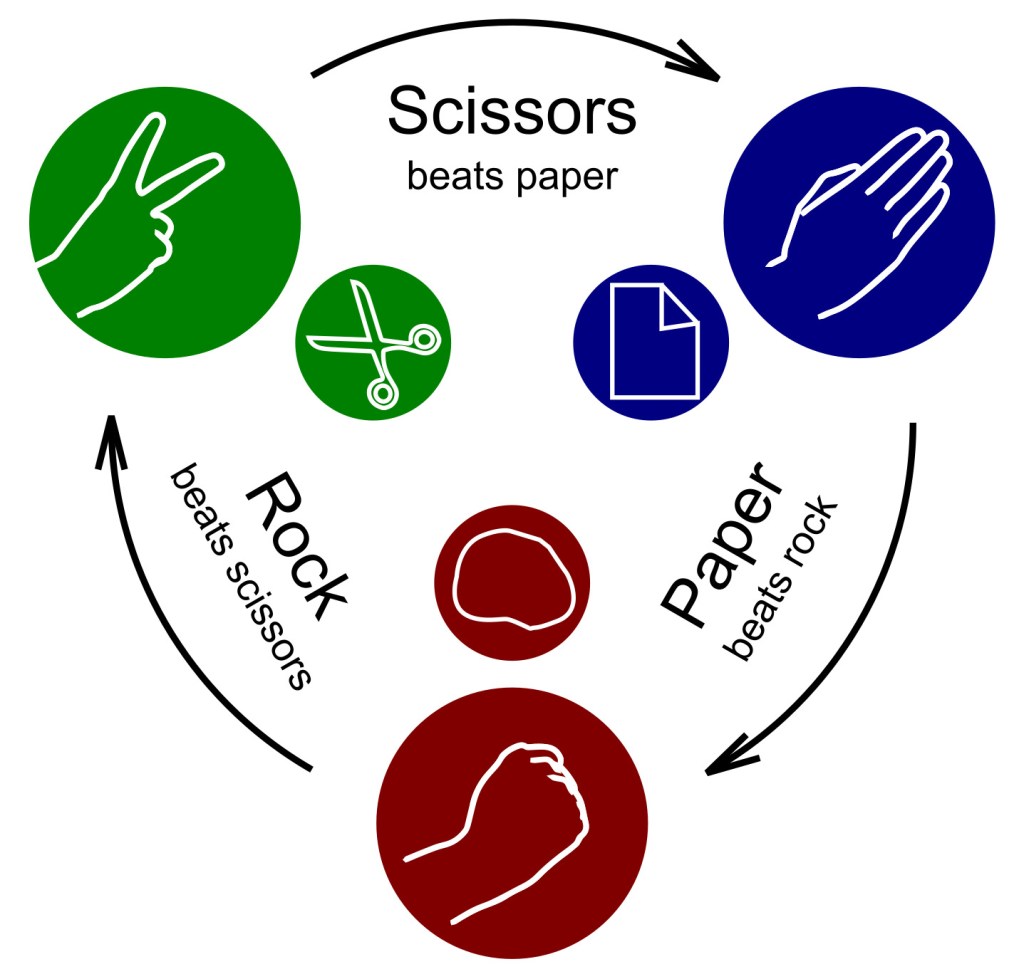

The US government has three branches—legislative, executive, and judicial. We use the analogy of the rock-paper-scissors game to show how the Framers of the Constitution intended for these three branches to check and balance each other.

Here’s how this arrangement was supposed to work. Imagine that:

• Congress is paper;

• the president is scissors; and

• the courts are rock.

In this scenario, Congress issues paper—or a law—which the president can use scissors—the veto—to cut. The courts can use a rock—declare the president’s action unconstitutional—to smash the president’s scissors.

This game analogy isn’t perfect, since with enough votes, Congress can limit the president’s power by overriding a veto and passing a law anyway. The courts can declare a law unconstitutional, and Congress can’t overrule them. Furthermore, Congress can impeach and convict the president.

But the Framers assumed that this three-part system would work, based on the checks and balances they built into the Constitution. That’s because they also assumed that each branch would play its assigned role and not overreach too much.

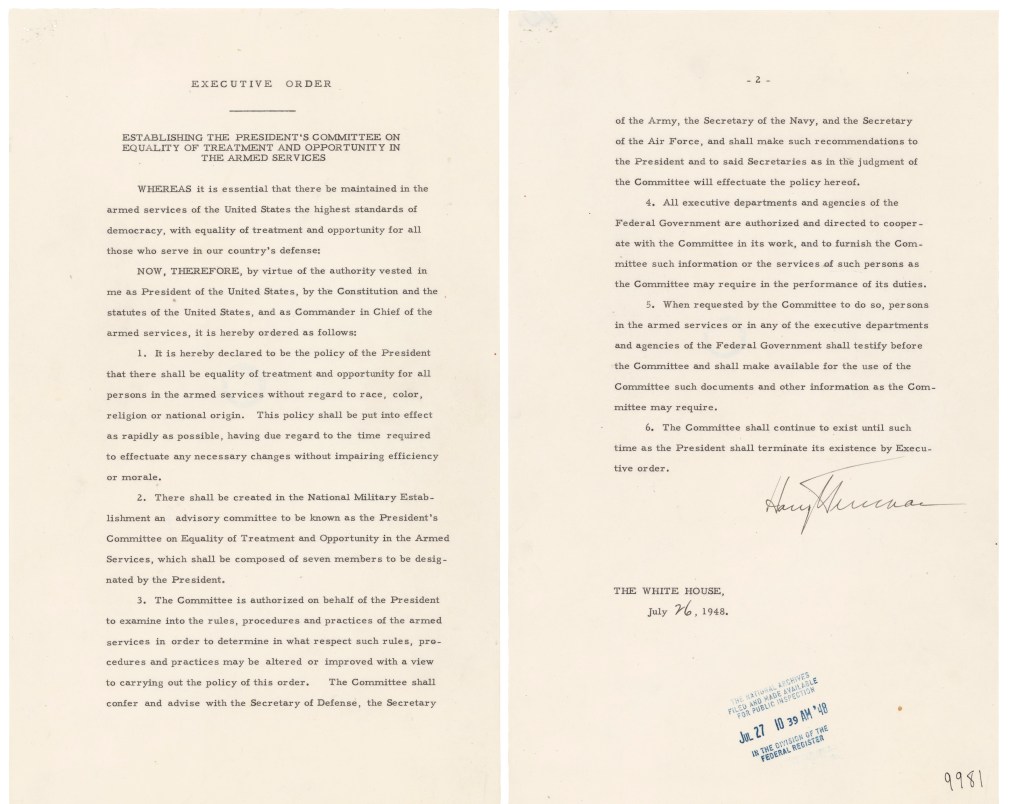

However, the second administration of President Donald J. Trump is playing out differently from the way the Framers expected. By issuing executive orders—152 to be exact, as of May 28, 2025—Trump is doing an end run around Congress. Many of the orders have the force of laws that Congress did not pass or even consider adopting. Other executive orders cut funding and staff for programs established by laws that Congress did pass.

Why is Congress allowing the president to usurp its powers? There are a couple of reasons. One is that a majority of the members of the 119th Congress are Republican like the president, and they either agree or don’t want to disagree with him. The Framers didn’t predict—and wanted to prevent—the formation of political parties.

Above all, Trump is taking full advantage of assuming the role of what’s called “the unitary executive.” This is the idea that the president controls all of the executive branch of government, including every one of the more than three million people who work for the White House, the president’s cabinet, and all of the agencies and subagencies. (We discuss the unitary executive in more detail in Chapter 14 of the third edition of Fault Lines in the Constitution.)

Most presidents issue executive orders, but Trump has expanded his power more than any previous president by using them to fire tens of thousands of employees who carry out the projects that the majority of congresspeople said they wanted. These staff members are considered civil servants rather than political appointees, who come and go with each new administration. Thanks to the Pendleton Act, passed in 1883, they are supposed to be—and have in the past been—protected from being fired or let go for political reasons. Without essential staff, important programs wither, and sometimes even vanish. A few examples of those whose funding and staff been slashed or entirely ended include:

• Head Start, which provides support for young children from families with low incomes;

• the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), which provides food and medical care for impoverished people around the world;

• the National Institutes of Health, whose funding supports scientific research at universities and federal laboratories and hospitals;

• the Department of Veterans Affairs, which provides healthcare and other services for military veterans; and

• the National Space and Aeronautics Administration (NASA) whose scientific research and Moon programs are being reduced.

By asserting that he can diminish or end these services, Trump is demonstrating his belief that he is the unitary executive—the boss of everyone underneath him, no matter how far down they are in the chain of command. Because the president is also the commander-in-chief of the armed forces, this raises the question of whether every soldier, sailor, pilot, marine, coastguardsman, and Space Force guardian also reports to him. Do they have to follow his orders, even if they think they’re unwise or illegal or contradict those of their superiors? If they do not, what repercussions might they fear or expect?

In February 2025, Trump stated on social media platforms, “He who saves his Country does not violate any Law.” Such an autocratic statement, declaring that a leader can break laws passed by the people’s representatives in Congress, runs counter to the views of the Framers, In Common Sense, an influential pamphlet published prior to the Declaration of Independence in 1776, Thomas Paine emphasized the importance of overthrowing monarchs. The United States should be a republic controlled by “we the people,” he said, with citizens possessing “inalienable rights” rather than being subjects of a king with uncontrollable power.

Paine had his opponents, even among those who framed the Constitution. Alexander Hamilton advocated for an elected rather than a hereditary monarch. Hamilton assured Americans that that person would differ from a king because he wouldn’t inherit the position; he would be chosen by the people. In any case, Hamilton promised that the Electoral College would prevent an unsuitable person from being elected president.

After having their staff fired and their funding cut, many individuals, organizations, and private entities, including at least one university, have sued the president or members of his administration. This is how the third branch—the courts—gets involved. Cases are working their way through the judicial system so we don’t know yet whether or how much this branch will check President Trump, the unitary executive.

Meanwhile, there’s another analogy that might help you visualize the ways that the three branches of government have shared power to maintain our democracy. That is a three-legged stool. One leg is now severely weakened, since Congress is largely doing the president’s bidding. It remains to be seen whether a stool that’s resting on one rigid leg, an uncertain one, and a feeble one can remain standing.