“. . . Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed. . .” —Declaration of Independence

In the introduction to Part I of Fault Lines in the Constitution we list the three parts or branches of the federal government:

• the legislature (Congress, made up of the House of Representatives and the Senate, both of which are voted on by “the people”)

• the executive (the president)

• the judicial (the court system, headed by the Supreme Court)

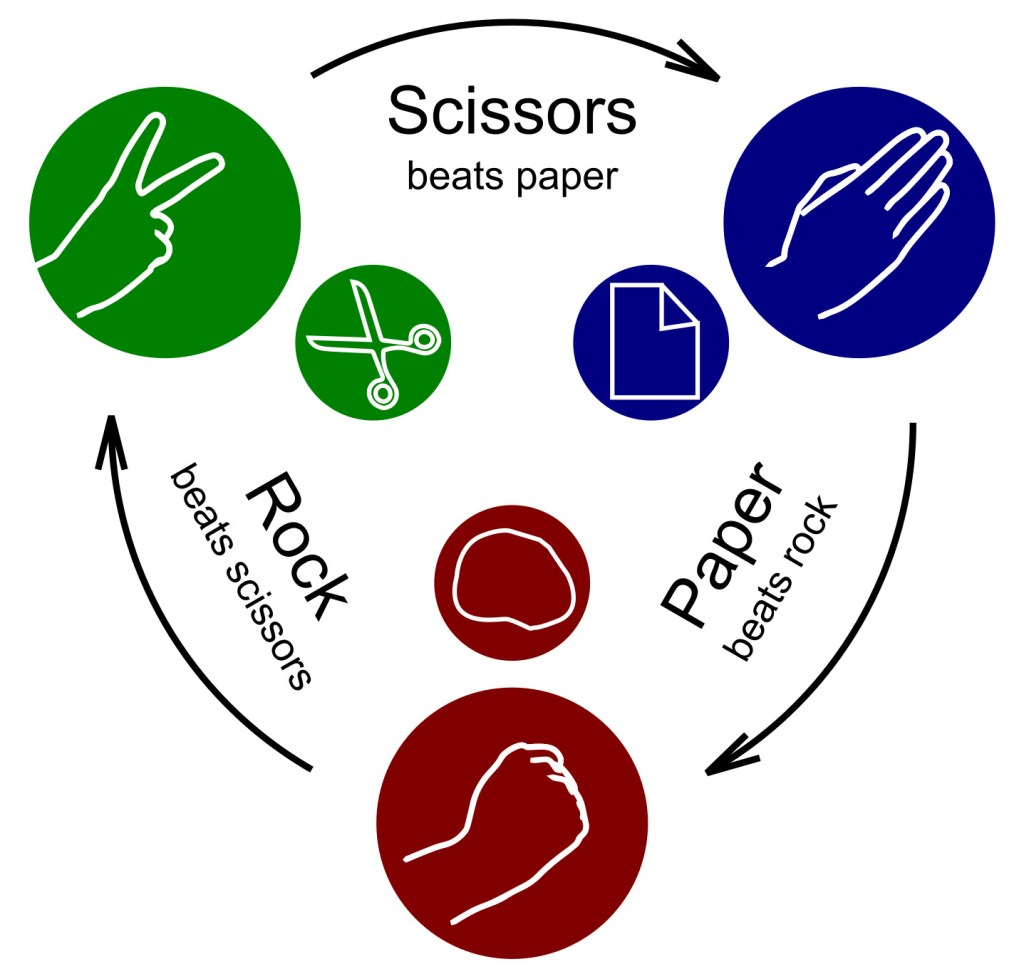

This arrangement, called separation of powers, makes some sense. The checks and balances system among the branches is similar to the rock-paper-scissors game in which each player has some power over the others but none necessarily dominates the others.

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Rock-paper-scissors.svg

You might have learned about this structure, which the Framers of the Constitution devised in 1787, in a social studies class. Since the book focuses on fault lines or cracks in the foundation of our governmental system, we don’t illustrate how it works, though. On the contrary, we show where it breaks down, giving examples of how the flaws play out in our daily lives today.

Throughout the book, we describe tensions among the Framers as they debated whether and how to balance the three branches they came up with. They wondered

• how many presidents should there be?

• who should choose him (the Framers assumed all presidents would be male)—or them?

• how long should he or they serve?

Shortly after beginning their deliberations, a majority of the Framers voted to have Congress select the president. Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts disagreed because the plan would give too much power to that body. He proposed instead that state governors vote for the president. Hugh Williamson of North Carolina wanted three presidents simultaneously from different parts of the country, all in office for twelve years. Alexander Hamilton wanted an “elected monarch,” chosen by electors, who would serve for the rest of his life.

The Framers also considered

• whether the president should be able to veto bills passed by Congress

• and if so, what kinds of bills could he veto—only those that he believed to be unconstitutional or any he didn’t like?

Hamilton wanted to give the president an absolute veto over all bills. Pierce Butler of South Carolina feared that would turn the president into a dictator.

The Constitution was intended to resolve these and other debates with our checks and balances system. When in doubt, though, about which branch should prevail, James Madison wrote, “In republican government, the legislative authority necessarily predominates.” He wasn’t referring to the Republican Party, which didn’t exist then. The Framers hoped desperately to avoid parties altogether. By “republican government,” Madison meant a country in which citizens vote for their leaders. And their elected leaders in Congress should be the top dogs because they represent the people.

As we explain in Fault Lines in the Constitution, things have not gone as the Framers imagined, partly because parties quickly arose. Recently, President Donald J. Trump has leaned heavily on the executive side of the balance scale, sidelining the people’s representatives in Congress. How? Through several mechanisms, beginning with executive orders. These are written directives from the president ordering a government agency to undertake or stop certain actions.

Article II of the Constitution requires that the president “take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed.” Since the time of George Washington, presidents have interpreted this language to mean that they can—and should—issue executive orders (EOs) to be sure that laws are carried out. Since EOs are intended to implement laws, orders cannot override or contradict laws, no matter how much presidents wish they could.

During the first month of his second term, President Trump signed seventy EOs, giving ultimatums on immigration policy, curricula in public schools, aid to other countries, and many more. By his eighteenth day in office, he was up to fifty-three. During his first term, Trump issued about 180 EOs. These are not comparatively high numbers. In eight years in office, Woodrow Wilson issued 1,803 executive orders. And, over twelve years, Franklin Roosevelt issued 3,721!

And presidents have caused major changes this way. Harry Truman integrated the military with an EO in 1948. Abraham Lincoln freed enslaved people in 1863 with the EO called the Emancipation Proclamation.

Source: https://lccn.loc.gov/2003655765

Trump’s actions, though, are viewed by many people as a fundamental game changer in the balance of power between the presidency and the people. He could be causing not just a “constitutional revolution,” as it’s been called, but a total upheaval in the Articles in the Constitution that lay out the separation of powers. A major reason is that many of his executive orders, such as those that stop funding for programs created by Congress, undermine or contravene laws that the people’s representatives passed. Rather than carrying out those laws, the president, a Republican, is preventing them from being implemented. And rather than objecting, Republican senators and representatives, who hold the majority of the seats in both houses, are remaining loyal to him, accepting the fact that the executive branch is dominating the legislative branch. Democrats are in the minority and haven’t found or agreed on a strategy to assert Congress’s constitutional powers.

Americans who want a heavy-handed executive see Trump’s orders positively. Those who prefer a more evenly balanced system, in which the voices of the people are not drowned out by the president’s, are deeply alarmed.

love this, thank you for sharing, I still use your book in my classroom after you sent it to me two years ago…

Sincerely,

Jim Guy

LikeLike

esteemed! World’s First Human-Machine Hybrid Olympics Announced 2025 captivating

LikeLike