The United States has one of the lowest voter-turnout rates in the world. Just slightly more than half of eligible voters go to the polls every four years to vote for president. Even fewer show up for midterm congressional elections, let alone for interim state or local issues, such as school or highway bonds, referendums, or choosing county judges or city council members. As we explain in Fault Lines in the Constitution, there are many reasons for Americans’ low rates of voter participation, including complicated requirements for identification and difficulty in registering. Another reason is inconvenience.

Although the national Constitution and some congressional statutes place limits on states, they still retain significant leeway to pass their own voter eligibility laws. For instance, three dozen states require voters to present various kinds of identification. And more than six million people can’t vote because of their criminal records; some of them haven’t even been convicted. Moreover, every city or county gets to determine its own particular arrangements, such as the location and number of precincts and the hours they’ll be open.

An especially vexing inconvenience for voters is that elections for national office take place on the first Tuesday in November. The Constitution gives Congress the power to decide the “times, places, and manner” of congressional and presidential elections. Back in 1845, that body chose Tuesday. Why?

Some historians say the reason has to do with farmers and the slow pace of their horses and buggies. Prior to 1845, states could choose their own voting dates anytime during the thirty-four days before the first Wednesday of December. That was the day Congress had picked for the Electoral College to meet in every state. It took days to collect and count the votes within a state. Then, more time was needed to compile those results and transmit them to Washington, DC. Some people thought that states that voted early could influence the outcome of the national election; others believed that late voting states could do the same. A single election day removed any possibility of gaming the system. (These days, however, states such as Iowa and New Hampshire compete to be the first to hold their presidential caucuses or primaries to throw their political weight around.)

When federal lawmakers finally decided to standardize Election Day, they rejected Monday because, to get to the polls in time, farmers would have to hitch up the horse and set out on Sunday, the Lord’s Day. That wouldn’t do. Wednesday was out because that was when farmers sold their produce at markets in many communities. Tuesday fell in between. Done!

When federal lawmakers finally decided to standardize Election Day, they rejected Monday because, to get to the polls in time, farmers would have to hitch up the horse and set out on Sunday, the Lord’s Day. That wouldn’t do. Wednesday was out because that was when farmers sold their produce at markets in many communities. Tuesday fell in between. Done!

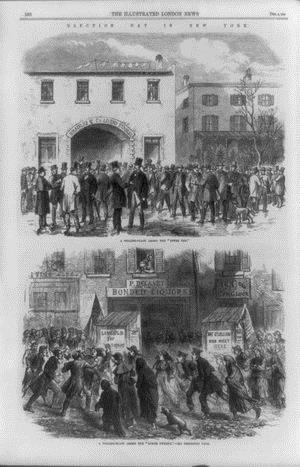

This print at the Library of Congress comes from The Illustrated London News of December 3, 1864. It depicts Election Day in a wealthy (top) and a poor (bottom) neighborhood, both in New York. The top caption reads: “A polling-place in the ‘upper ten.’” The bottom caption reads: “A polling-place among the ‘lower twenty.’” (https://www.npr.org/sections/itsallpolitics/2012/10/23/162484410/why-are-elections-on-tuesdays)

It’s been done and settled for the past almost one-hundred and seventy-five years, even though most people now work at jobs that don’t give them time off on Tuesdays to stand in line at the polls.

Some states and many other countries have gotten around this problem in creative ways. Early voting, available in Texas and other states, allows voters to cast their ballots on a day they choose, up to several weeks before the official Election Day. Everyone in Oregon votes only by mail. West Virginians who live overseas successfully experimented with a blockchain voting app in the 2018 midterms. And, the small town of Sandusky, Ohio, recently decided to give city employees a holiday on Election Day instead of Columbus Day. Most other countries, however, hold elections either on Saturday or on a designated holiday when, presumably, most people are not working.

In fact, a bill before Congress proposes to make Election Day a national holiday so that most workers could get time off to vote. Known as HR1, it would also give federal employees paid leave to help out at polling places.

In fact, a bill before Congress proposes to make Election Day a national holiday so that most workers could get time off to vote. Known as HR1, it would also give federal employees paid leave to help out at polling places.

Some Republican legislators oppose the measure. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky responded, “Just what America needs. Another paid holiday and a bunch of government workers being paid to…hover around while you cast your ballot.” McConnell’s home state allows government employees to get the day off to vote in presidential elections.” Opponents also point out that turnout is not higher in states that provide such programs. Above all, they complain (and fear) that these measures would aid Democrats more than Republicans. Retirees, for instance, many of whom are Republican, can vote on any day of the week. On the other hand, federal employees in the District of Columbia, many of whom are Democrats, might vote in a manner that benefits their party if they don’t have to work on Election Day.

Underlying these debates is the question of whether the government should make it easier for people to vote by changing long-established practices, such as Tuesday elections. What do you think?

Our fellow citizens are abandoning the GREATEST PRIVILEGE that we in the USA have: the right to vote! Let’s all of us go to the polling places and VOTE, VOTE, VOTE. Elect a thoughtful, intelligent, passionate person to represent all of us for a healthy and strong democracy!

LikeLike