In May 2017, the Deputy Attorney General of the United States, Rod Rosenstein, appointed Robert S. Mueller III to look into whether or not President Donald J. Trump’s staff had worked with people in Russia during the presidential campaign in 2015 and 2016. As special counsel, Mueller was given the job of determining whether they had tried to influence the outcome of the election. Doing so would break US laws.

Rosenstein took this action for a number of reasons. In particular, he learned that some of Trump’s aides began meeting with Russians several months after he announced he was running for president in 2015. In addition, some of Trump’s foreign policy staffers knew that Russians had hacked into the email server of his opponent, Hillary Clinton, and then made her emails public. In numerous tweets and speeches, however, the president has steadfastly denied that his campaign colluded with Russia to help him win the election.

To find out whether or not US election laws were broken, Mueller has been interviewing Trump’s associates. Some of them have provided information about meetings they had with Russians, and the president has strongly criticized these staffers. He even fired the head of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, James B. Comey, for refusing to promise to protect him during Mueller’s probes. As a result, Mueller is also looking into whether Trump has tried to influence or derail his work as special counsel. If the president did so, that could mean he is guilty of obstructing justice. Trump has denied this charge also.

Several times during the spring of 2018, President Trump mentioned the possibility that he might fire both Rosenstein and Mueller, possibly as an effort to end the special counsel’s investigations. In one of our previous blogs, “You’re Fired!” “Oh, No, I’m Not,” we pointed out that the president has the right to fire just about anyone who works in the executive branch of the federal government. Both Republicans and Democrats, however, want Mueller to continue his work. Two senators from each party joined together and introduced a bill into Congress that would protect him from being let go. The legislation says that a special counsel can be dismissed only for “good cause” and only by a senior official in the Justice Department. In addition, the special counsel could have the firing reviewed by a judge.

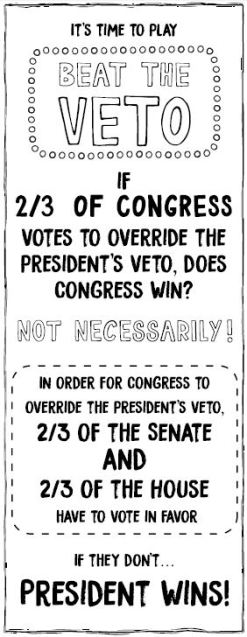

There are several reasons this bill might not pass. The major reason relates to a fault line in the Constitution. Article I, Section 7 gives the president the power to veto any legislation passed by Congress. To overcome a veto, two-thirds of the members of both houses must vote to do so. That’s not two-thirds of Congress. That’s two-thirds of the House of Representatives—288 people—and two-thirds of the Senate—or, 67 people. It’s so hard to get a super-majority of both houses to agree on just about anything that, over the past two hundred and twenty-five years, presidents have succeeded in vetoing legislation they don’t like 95 percent of the time.

Americans say that we have a bicameral system, consisting of two houses of Congress, to pass bills. Because of the president’s ability to veto legislation, however, some people argue that we actually have a tricameral system—two houses to pass bills and one person to keep them from becoming law.

We also refer to our system of government as one of checks and balances. But, the veto gives the president a very powerful check on Congress. Even if a hefty majority of both the House and the Senate, with the support of the public, want a law that the president does not, they won’t get it without support from two-thirds of both houses.

We also refer to our system of government as one of checks and balances. But, the veto gives the president a very powerful check on Congress. Even if a hefty majority of both the House and the Senate, with the support of the public, want a law that the president does not, they won’t get it without support from two-thirds of both houses.

No one knows whether a majority of senators and representatives want to pass a bill to protect the special counsel from being fired by the president. It is unlikely that two-thirds of them do. So, many of them argue that there’s no reason to bring the bill up for a vote. As Republican Senator Mitch McConnell pointed out, “Even if we pass it, why would he [Trump] sign it?”

Presidential vetoes can be essential if Congress passes crazy legislation. Or, they can be a serious problem if the president becomes overly powerful. What do you think? Should the president be able to veto acts of Congress? If so, should Congress need to amass a super-majority to overcome a veto?

Even the most well-designed constitution isn’t safe from a president committed to subverting it, as we see today in Poland as well as in the U.S. Were this provision to change (which is nearly impossible to in the case of the U.S. Constitution), would-be autocrats would soon figure out a work-around. We need to identity the tools we have to preserve the rule of law against an executive dedicated to undermining it, not only elections but also the rights to freedom of speech, press, assembly, and petition that too many people (and especially the large media companies) seem to be giving up voluntarily.

LikeLike

As usual, these are excellent points, Lyn. It’s astonishing how much power a president can wield, even one with a low approval rating.

LikeLike

A reminder that America is a government of laws, not of men (now including women). But it is men and now women in government who apply and enforce those laws, and Genesis’ “original sin” might remind some people of the frailties of men and women. Those of us old enough to have lived through Nixon’s Watergate faced similar issues to what we face today with Trump. Perhaps those too young to have gone through and understood the public’s travails of Nixon’s Watergate need to revisit those days to perceive the threats to our democracy under an imperfect Constitution to see that over time the Constitution worked.. Hopefully the Constitution will work again. Some cynics might point to the reactions of some men and women to Bryan Stevenson’s museum about lynchings of African Americans post-Civil War through much of the 20th century who do not wish to be reminded of America’s “original sin” while whistling Dixie. If America fails, then in the words of the late Walt Kelly’s Pogo, “We have met the enemy and he is us.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sage words, Shag. Thank you.

LikeLike

In theory, the solution to the problem of an irresponsible or unwise presidential veto is to wait it out until the president’s term expires and then re-pass the bill when a friendlier president is in office.

Yet it seems in American history that oftentimes an idea has its moment and then fades away and cannot be revived even after the president who vetoed the legislation is gone. Two important examples of this are John Tyler’s veto of the Third Bank of the United States and Andrew Johnson’s veto of civil rights legislation.

In both examples, the ideas became dormant, despite the US economic system was much less stable than that of European countries and black Americans being systematically victimized.

For all we hear about the American separation of powers, I do find it inconsistent that the president was given such a dominant role in approving legislation. If the executive is just supposed to _execute_ legislation, then why doesn’t the legislature have free rein to pass legislation?

Given the dynamic in the United States of divided government starting after a president’s first midterm, we have condemned ourselves to near-constant gridlock.

LikeLike

We completely agree, Sam. There are many examples to back up your point, including the loss of the Dream Act and of anti-lynching legislation, both of which had their moments, which then vanished. There’s also the problem that by the time we have a new president, there’s also a new Congress, whose members are not necessarily disposed to follow the desires of their predecessors. Thanks for commenting!

LikeLike