You might not have noticed but there’s been a lot of talk—and disagreement—in the media about whether or not our country is having a constitutional crisis. In less than a month, for example, we saw:

- “America is Heading for an Unprecedented Constitutional Crisis”

- “America is Nowhere Near a Constitutional Crisis”

- “This is a Constitutional Crisis”

Is there a crisis or not? And, what should we do if there is?

If a patient has a fever of 106 degrees, which won’t go down despite treatments, a doctor could say that person is having a medical crisis and might die. Similarly, a constitutional crisis would be a time when our government might not survive—when the fault lines cave in and create an earthquake. While a doctor might know when a patient is in such dire straits, how can we tell if the United States is facing such a calamity? It seems unlikely but it’s happened at least twice before, once at the very beginning of our country and again barely seventy years later.

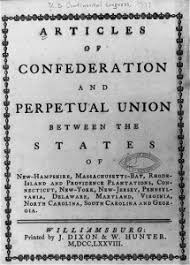

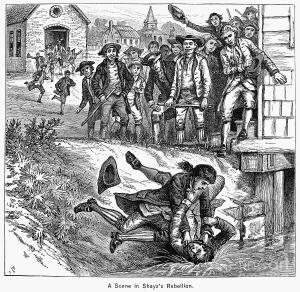

America’s first constitution, which went into effect in 1781, was called the Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union. Under this arrangement, each of the thirteen states sent delegates to a Congress to try to resolve disputes over issues like borders and soldiers’ pay. It didn’t work, though, because it had no teeth. Even when the delegates managed to come to an agreement, the folks back home could ignore it. Soldiers and farmers rebelled. Alexander Hamilton labeled the Articles “imbecilic.” George Washington said this “is not a government.” What this was, was a crisis.

|

|

So Congress called for a convention to revise the Articles. The delegates to that convention didn’t just revise them. They unconstitutionally scrapped them and started all over, devising the structure we rely on today.

There are several ways that structure could topple. (Sandy and a friend at the Yale Law School wrote an article, making somewhat similar points, in 2009.) Here are some hypothetical examples. As you read them, think about the purposes of the Constitution, as set out in the Preamble, and how they would be undermined.

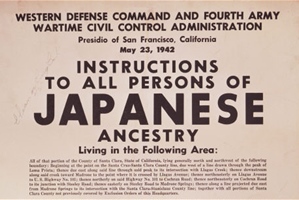

1. The Constitution doesn’t tell us what to do in times of trouble. The United States faces many potential threats—biological, technological, nuclear. If our major cities, water systems or electrical grid were attacked across the country, the president and Congress would have to make fast decisions. If the perpetrators are unknown, should the entire country be placed under curfew? Should people suspected of carrying out or supporting the attack be locked up, even if there’s no evidence they were behind it? This happened to Japanese-Americans during World War II.

Most of the 110,000 people who were rounded up and detained seemed to accept their fate. A man named Fred Korematsu, however, objected and sued the federal government. The US Supreme Court ruled against him. But what if the court had agreed with him and ordered everyone released—and then the president kept them imprisoned anyway in the name of protecting national security? According to the Constitution, the president is not allowed to thumb his nose at the Supreme Court, and citizens would undoubtedly be outraged if he did.

Open defiance of the law by a president would set up a situation in which the Constitution does not establish justice, insure domestic tranquility, or secure the blessings of liberty. In fact, it would be a crisis situation, especially if the public complained long and loud—and would probably amount to a full-scale constitutional crisis.

Open defiance of the law by a president would set up a situation in which the Constitution does not establish justice, insure domestic tranquility, or secure the blessings of liberty. In fact, it would be a crisis situation, especially if the public complained long and loud—and would probably amount to a full-scale constitutional crisis.

The example on which we based these questions is historical. But, could you imagine other groups being corralled today? What do you think the results might be?

2. What the Constitution tells us to do takes the country over a cliff. The Constitution establishes the president as commander in chief of the armed forces. Though the Declaration of War Clause in Article I of the Constitution seems to require him to get approval from Congress before acting, many (though not all) lawyers and members of the public believe this means that the president has the authority to take war-like actions without it. The United States has engaged in quite a few wars based simply on a president’s decision. As a result, this clause is practically a dead letter, even though no amendment has repealed it.

But what if a telecommunications glitch—like the kind that led Hawaiians to believe they were being attacked in January 2018—or even just a taunt from a foreign leader prompted our president to order the launch of a nuclear missile? There are at least two ways this scenario could lead to a constitutional crisis, depending on how the military interpreted the Constitution.

One would occur if the generals believed that the order was an unnecessary or bad idea—but they followed it anyway because they thought the Constitution told them they had to. The other could occur if the generals came to the opposite conclusion that the order was necessary but illegal because Congress has to declare war before they can take action—so, they didn’t.

In the first case, an almost blind adherence to the Constitution might lead to a catastrophic and unwarranted nuclear war. In the second, the military would be adhering to the Constitution by defying their commander in chief and waiting for Congress to approve the president’s order—but they might end up endangering the nation. Either way, it’s not clear that the Constitution would provide for the common defense or promote the general welfare. Thus, we might well have a constitutional, as well as a political and human, crisis on our hands.

In the first case, an almost blind adherence to the Constitution might lead to a catastrophic and unwarranted nuclear war. In the second, the military would be adhering to the Constitution by defying their commander in chief and waiting for Congress to approve the president’s order—but they might end up endangering the nation. Either way, it’s not clear that the Constitution would provide for the common defense or promote the general welfare. Thus, we might well have a constitutional, as well as a political and human, crisis on our hands.

Political or Constitutional Crisis?

A constitutional crisis is different from a political crisis. The Constitution, after all, is supposed to provide structures and guideposts for resolving political disagreements. Much of the time, it works, even if the losers in the political disagreements are unhappy or believe they were treated unfairly. Still, they accept the verdict and begin organizing for the next election.

But sometimes the Constitution does not work. People may not follow its guidelines because they believe the stakes are too high. After all, the Constitution did not prevent the attempted dissolution of the Union in 1861. The Civil War was certainly our greatest constitutional crisis.

As with medical treatment, it’s a good idea to take preventive actions to avoid reaching crisis situations where survival is uncertain. Perhaps thinking about circumstances that could lead to the breakdown of our governmental system again will suggest possible actions that could help us avoid repeating the devastation of Civil War or other breakdown of our constitutional government.

Regarding the medical treatment analogy, the Hippocratic Oath seems to have worked well over many centuries. Might the Preamble to the Constitution be considered a constitutional Hippocratic Oath in the interpretation/construction of the Constitution? Medical malpractice occurs despite the Hippocratic Oath. And the Constitution does not always resolve political crises. Both the Oath and the Constitution rely upon professionals. Alas, there are always human fault lines.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Shag, I like your analogy. Both the Preamble and the medical profession aim toward ideals. Both, alas, fail. And the failures in both are getting more expensive! But, in general, I tend to think that the practice of medicine and knowledge of the body are improving while the practice of the Constitution and the knowledge of the body politic are declining.

LikeLike

I’m curious. Wasn’t there a third party comment following mine (but unrelated to mine) that seems to have vanished? Can a commenter delete his/her own comment?

LikeLike

I don’t know the answer to your question, Shag. I need to ask our publisher who hosts our blog.

LikeLike

My error. I apparently clicked on an earlier archive than January, 2018. I have to be more careful. Sorry.

LikeLiked by 1 person

No problem!

LikeLike