Almost every chapter in Fault Lines in the Constitution opens with a story. With thanks to Virginia Hamilton’s Anthony Burns: The Defeat and Triumph of a Fugitive Slave, here’s one that didn’t make it into the book. It’s about a serious fault line and also about July 4.

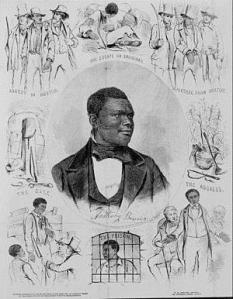

Walking along Boston’s Court Street on the evening of May 24, 1854, Anthony Burns, a black man, barely noticed the five men running up behind him until they picked him up and carted him off to the Court House where he was locked in a cell. He pleaded to be let go but his captors ignored him. Instead, the cell door slowly creaked open, and a man peered in.“How do you do, Mr. Burns?” the man slyly asked.

“Master!” the prisoner exclaimed.

This spontaneous outburst doomed Anthony Burns. He could not deny that he was a slave, that he belonged, not in the free Commonwealth of Massachusetts, but to this man, Colonel Charles F. Suttle of Alexandria, Virginia, from whom he had escaped three months earlier.

With the help of an intercepted letter Burns had written to his brother, Suttle had little trouble finding his property. He made his way to Boston and asked the US Marshal to arrest him. Even though Massachusetts was a free state, Burns was not a free man. Thanks to the Fugitive Slave Law, which Congress had passed in 1850, Suttle had more right to demand the return of his slave than he would a runaway horse.

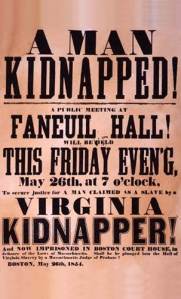

A local newspaper urged readers to “protest against this monstrous and atrocious wrong.” The next night, five thousand incensed citizens gathered at Faneuil Hall where, eighty years earlier, colonists had protested against King George III. Abolitionists tried to free Burns from jail and escort him to safety in Canada but they failed. They also tried to buy and then free him but Suttle refused to sell. After they lost a trial, President Franklin Pierce wired, “The law must be executed.”

On June 2, Burns trudged out of Boston, shackled at his ankles and wrists, to be returned to Virginia. An estimated fifty thousand sympathizers lined the route from the Court House to the wharf. Black bunting hung from upper-story windows. American flags flew upside down. An oversized coffin, inscribed “Liberty,” was raised overhead. Boston seemed to sink beneath the shame.

It had become starkly clear that, despite promises made in the Preamble, the Constitution did not “establish justice” or “secure liberty” after all. On the contrary, it perpetuated slavery. Worse, through compromises the Framers made in 1787, the Constitution built the numbers associated with slavery into Congress and the Electoral College. (We explain how in Chapter 5.)

On July 4, 1854, a month after Burns’ forced return, William Lloyd Garrison, the founder of the New England Anti-Slavery Society, and about two thousand others, gathered in Framingham, Massachusetts—not to celebrate but to demonstrate. Holding a furled Constitution in one hand and a lighted torch in the other, Garrison intoned, “The Constitution of the United States of America is the source and parent of all other atrocities: ‘a covenant with death, and an agreement with Hell.’” Then, he incinerated it.

Ten years and a Civil War later, the Thirteenth Amendment abolished slavery. For the first seventy-eight years of our country, however, legal ownership of human beings created its deepest and most disgraceful fault line.

Thank you for sharing this with us – I didn’t know about Anthony Burns.

I recently learned about Hercules who cooked for George Washington (in THE PRESIDENT’S KITCHEN CABINET: THE STORY OF THE AFRICAN AMERICANS WHO HAVE FED OUR FIRST FAMILIES by Adrian Miller.) Miller discusses how Washington moved kitchen staff back and forth from NYC to Virginia to ensure Hercules & others remained enslaved, since NY was a free state and if he stayed there beyond a certain amount of time, he would be free.

I knew Washington & other “Founding Fathers” were slave owners, but those time and travel details really etched into my brain the lengths the President went to in ensuring his property rights. And made me see him in a new light.

Likewise, after reading your chapter on representation, I understand that the “three-fifths compromise” gave a tremendous advantage to the Southern slave-holding states, ensuring they would have the upper hand in any proposed legislation relating to slavery (not surprisingly I don’t recall it being explained quite so plainly in civics class.)

LikeLike

Thank you, Gayleen, for your very thoughtful response. In regard to GW’s slave Hercules, I knew only of the picture book A Cake for George Washington, which met an undeserved end. The Miller book sounds fascinating. Most people do not know the origina of the 3/5 clause and despise it, both appropriately and for the wrong reason. Keep stopping by. We’ll be posting updates to Fault LInes in the Constitution every two weeks.

LikeLike

Afraid I must correct you. New York was still a slave state during Washington’s time their as President. Only in 1791, when the capital moved temporarily to Philadelphia, which was in the “Free State” of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Pennsylvania having adopted gradual emancipation in 1780 in the grip of revolutionary fervor. However, even 1791, there were still slaves in Pennsylvania and the legal status of Washington’s slaves as slaves was not the problem. The problem is that there was a free black community and a strong white abolition community in Philadelphia that had come to include Benjamin Franklin. As a result, it became much easier for Washington’s slaves to escape with a large part of the populace not sympathetic to slave owners claiming their rights. It was to reduce these opportunities that Washington began rotating his slaves between his residence in Philadelphia and Virginia. Washington’s own attitude toward slavery was changing although not enough to emancipate slaves while he lived.

Emancipation in the North, particularly in the mid-Atlantic states outside Pennsylvania, was slow and had not been completed until the 1840s in New Jersey and New York.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for the clarification and for joining our conversation. (This issue is not discussed in Fault Lines in the Constitution but has come up in response to the book Gayleen referenced.)

LikeLike

Thank you for this story! Despite the Thirteenth Amendment, slavery continues to haunt the country as its Original Sin. Did you see Ava DuVernay’s award-winning documentary, 13th, which talks about how the criminal justice system has served as a means of re-enslavement from the end of the Civil War to the present?

LikeLike

Yes, 13th is a brilliant, important movie–and much better than Selma, which infuriated me.

LikeLike

If the 3/5 compromise never happened, neither would the Constitution’s ratification. Debating the value of that ratification is for another time and place. Had the Northern states give full count to slaves at the time, it may well have been the North that eventually seceeded to start the Civil War. Perhaps it’s time for another Constitutional Convention so we can create a perfect Constitution. Our elected leaders certainly know what they’re doing these days!

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s a very interesting point about the North seceding if slaves had been fully counted. In regard to another Constitutional Convention, my husband/co-author and I engage in a debate about that in the last chapter of the book.

LikeLike

That our founders were so enlightened and yet (some of them) still owned human beings as property is a dichotomy at our nation’s very heart. According to interviews, the actors in the musical “Hamilton” struggled with it; for me, one powerful moment in the musical is at the opening of the second act where the character of Jefferson, played by an African-American, calls out, “Sally, bring me a pen” and suddenly the whole thing crashes in on itself: he’s talking to his slave, Sally Hemings. How could Washington and Jefferson justify their actions to themselves? It’s hard to square our notions of them as “heroes” with the fact that they were slave masters at the same time. But we must. It’s part of our legacy.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, that line of Jefferson’s is chilling, especially since we know Hemings wasn’t just his slave. There’s another line, which I don’t recall exactly, in which Hamilton ripostes (is that a verb?) to Jefferson during their debate about a bank pointing out who’s actually doing the planting on Jefferson’s plantation. The revelations I’ve read recently about Washington moving his slaves around so that they wouldn’t be eligible to be freed. I agree with you about the conundrum of their being deeply flawed heroes.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I had not known about Washington moving his slaves around deliberately so they would not be freed. The awareness that shows — “I don’t want to lose my property” — is, again, hard to square with the “Father of our Country” heroic image.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Indeed.

LikeLike